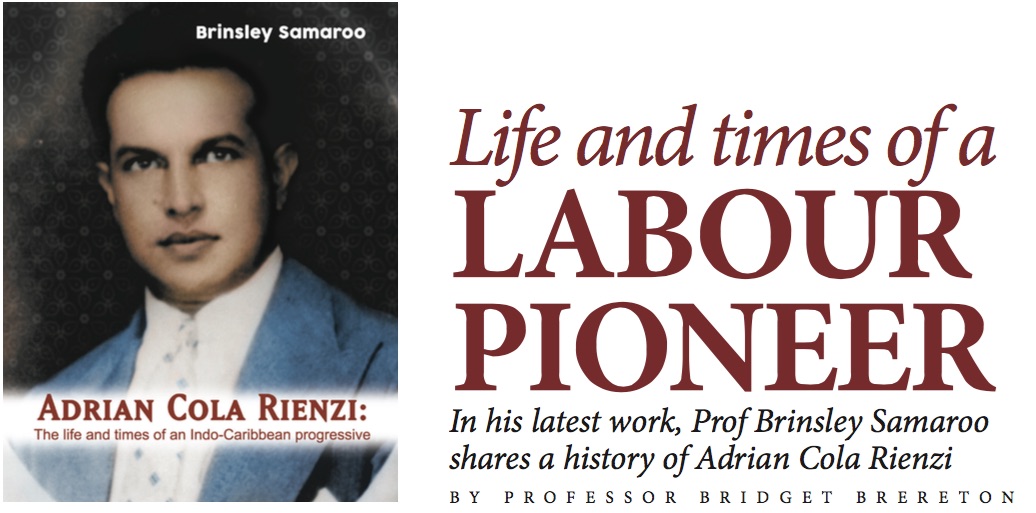

The wait has been long for a properly researched biography on Adrian Cola Rienzi—for decades the only serious publication about him was a pioneering journal article by Kelvin Singh, which appeared as long ago as 1982—and he has now gotten it. Retired UWI (and UTT) professor Brinsley Samaroo has just published Adrian Cola Rienzi: The life and times of an Indo-Caribbean progressive. Full disclosure: I read a draft of the book and I am thanked in the author’s Preface.

This book is a well-researched study. Samaroo has mined several primary sources: T&T newspapers and periodicals from the 1920s to 1940s; the Colonial Office files in the UK National Archives; the British trade union archives held at the University of Warwick; the T&T Hansard for debates in the Legislative Council; the San Fernando Borough Council Minutes; and more. Perhaps most important, he had access to the collection of papers, books and pamphlets amassed by Rienzi and held by his family. Though this is an academic study with the usual citations and references, Samaroo’s style is accessible and engaging, and the book is very readable.

It must be said that this is not a conventional biography which normally follows its subject’s life in a straight-forward chronological sequence. The chronology within and between the different chapters is sometimes a little confusing, and Samaroo often digresses from Rienzi’s life story to write about other, related topics—definitely “life and times”. But the digressions are interesting in themselves and don’t hold up the main narrative for long.

Krishna Deonarine was born in 1905, the grandson of indentured immigrants from India; he grew up in the sugar village of Palmyra in the south. His father ran a shop in San Fernando which had been established by his paternal grandmother, and the young boy was able to attend Naparima College. But money was tight, and he was forced to leave the school after only three years there. The teenager then went to work with the L.C. Hobson law firm in San Fernando, first as an office boy, then as a clerk.

Young Krishna was remarkably active in the public and political sphere in the 1920s, despite his youth. He became president of the San Fernando branch of Cipriani’s Trinidad Workingmen’s Association in 1925, at the age of twenty; he was on the executive committee of the East Indian National Association; he founded the Indian National Party around 1928; and he wrote letters to the press. All this got him noticed by the governor, especially when he sent a cable to the USSR congratulating the Russian government and people on the tenth anniversary of the 1917 Revolution. The governor noted his “markedly seditious views” and complained of one or two letters to the press “of a violently anti-British character”. So began decades of close surveillance by local and British security forces. In 1927, Krishna Deonarine officially changed his name to Adrian Cola Rienzi, adopting the surname of a medieval Italian radical whom he admired. It was undeniably a strange decision, one for which he was publicly attacked decades after his death by the now late Sat Maharaj.

With financial help from his employer, Hobson, Rienzi went to Dublin in 1930, studying for a year at Trinity College there, and then enrolled in the Middle Temple, London, to qualify as a barrister. In both Dublin and London, he got involved in demonstrations and meetings in support of Indian independence, and was influenced by the Indian Communist ex-MP Shapurji Saklatvala. All this ensured that he was closely surveilled by the British police. When Rienzi returned to Trinidad after being admitted to the English bar in 1934, it was said that the police dossier on him travelled on the same ship that he did. As a result, there was trouble getting him admitted to the local bar because of reports of his “seditious and revolutionary” activities in Dublin and London, and intervention by a high-level British Labour politician was required to ensure his admission.

In the decade between 1934 and 1944, Rienzi was active on many political fronts. Like Cipriani, he operated in three main domains: he was a member of the San Fernando Borough Council and served as Mayor for some years; he was an elected member of the Legislative Council for the county of Victoria between 1938 and 1944; and he was a prominent trade union leader at the very birth of the labour movement here, serving as the first president of the Oilfields Workers’ Trade Union and of All Trinidad (sugar workers’ union). Samaroo provides detailed accounts of all these activities during this crowded and crucial decade.

Especially valuable, in my view, are the careful and detailed sections on the events of June/July 1937 and the immediate aftermath (pp. 56-70); on the important Arbitration Tribunal in January 1939 which awarded a modest wage increase to oil workers (pp. 81-87); and on the birth of the OWTU and All Trinidad (pp. 92-99). These sections present information on these developments not easily available anywhere else. Chapter 6 analyses Rienzi’s work in the Legislative Council, based on the official record (Hansard), and his struggle for universal adult suffrage without any English language test, which would have disenfranchised many older Indo-Trinidadians.

In May 1943, Rienzi was appointed a member of the Executive Council, to the great delight of the Labour movement and the predictable dismay of the business and planter elites. But then, just a few months later, in February 1944, Rienzi resigned from the Executive and Legislative Councils and became a civil servant, accepting a salaried post as Second Crown Counsel. To my surprise, Samaroo offers no explanation for this abrupt and certainly controversial decision. It meant his exit from political and trade union activities for the rest of his life (he retired in 1965 and died in 1972).

Samaroo has done well to document the life of this important figure in T&T’s history during a crucial period; his book should be widely read and placed in the libraries of the country’s secondary schools and universities.