During and after the recent election campaign in Trinidad and Tobago, hostile messages with racist overtones proliferated the physical and virtual spaces of the nation.

To address these enduring underlying race issues, The UWI’s Faculty of Law in collaboration with the Catholic Commission for Social Justice hosted a virtual National Symposium on August 30 entitled A Time for Healing - Understanding and Reconciling Race Relations in Trinidad and Tobago. Professor Rose-Marie Belle Antoine, Dean of the Law Faculty, noted that public education on race was contemplated even before the election, but the election and a subsequent approach from CCSJ provided a timely opportunity to engage. She reminded that the UWI, as emphasised by Vice Chancellor Professor Sir Hilary Beckles and St Augustine Campus Principal Professor Brian Copeland, must be activist and centred in the community. Antoine saw the symposium as positioning The UWI as a facilitator of national discourse for the public good and a thought leader, using research and analysis as key tools.

“Elections and the post-election period are particularly difficult times for us,” said the featured speaker, sociologist Rhoda Reddock, Emerita Professor and former Deputy- Principal of UWI St Augustine. She said this was “a symptom of living in a racially polarised, post-colonial society”.

The symposium brought together panelists from academia, law, politics, the media, the arts, labour and youth. CCSJ Chair, Leela Ramdeen moderated the event which opened with prayer from representatives of various faiths. Justice Donna Prowell-Raphael, Judge of the Equal Opportunity Tribunal, explained its scope and jurisprudence on race discrimination.

Prof Reddock, also a member of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, said that the election’s racist overtones were predicated on two specific stereotypical narratives: that citizens of African descent are at the bottom of the economic pile and citizens of Indian descent receive certain privileges which allow them to progress.

Race relations in Trinidad and Tobago began with the near decimation of First Peoples, the enslavement of Africans, and then the immigration of indentured Indians. Subsequently, other non-European groups were introduced into an already racialised, colour-coded hierarchical structure. In pluralistic, polarised societies like Trinidad and Tobago, the stereotypes and dangerous myths generate little real understanding of the complex historical, socio-economic and cultural forces underpinning the country, she said. She observed that the election provoked “outrage” by middle-class Afro- Trinbagonians about images of Afro-descendant victimhood, but “many forgot that it was Afro-descendants themselves who were responsible for the myth of Afro-descendant victimhood” and “it was okay for Afro-Trinidadians to criticise their own.”

She continued: “The power of myths and stereotypes encompass aspects of truth... but they need to be challenged if we are to bring ourselves back from where we have arrived.” For example, she rebutted the much repeated myth that only Indians got land after emancipation. Historical evidence shows that Afro-descendant groups, including the Merikens, demilitarised soldiers and squatters did as well, and Indian land was given instead of promised repatriation grants.

Trade Unionist David Abdullah agreed that the colonial legacy encompassed a myriad of systemic issues, impacting the capitalist economic system. He warned that we must all fight “to humanise” our “geographic space”, while decrying the hierarchy that oppressed, non-white racial groups continue to bear.

Professor Antoine, former Rapporteur for Afro- descendants and Against Discrimination, Organisation of American States, focused on hidden forms of racism and discrimination in law. She highlighted existing indirect/ structural discrimination and systemic racism, especially in relation to economic, social and cultural rights like education, employment and health. She identified an unequal society exacerbating discrimination; and racism fueling inequality, citing intersectionality when different forms of discrimination interact with class and poverty.

Prof Antoine warned that the law does not require intention to discriminate, but can intervene if the result is disproportionately adverse to an ethnic group. She suggested meritocracy as a potential mechanism for redress, despite meritocracy being challenged by the inability of all groups to compete equally (eg education) and a recognition that there is more than one historically oppressed people. Innovative constructs must be found that focus on desirable outcomes.

She concluded: “If we are committed to equality among every creed and race, we must go beyond the surface and challenge the status quo, to confront these destructive, hidden racialised patterns and stereotypes.”

Mr Kwasi Mutema, Chair of the National Join Action Committee (NJAC), contended that the racial tension which exists between Indo and Afro-Trinbagonians is a politically manufactured one, influenced by the colonial “white power structure” in the Caribbean. This tension is introduced and perpetuated to prevent Afro and Indo-Trinidadian unity and to ensure that political and economic power continue to be wielded by the few. This accounts for why racism, primarily between these two groups, is overtly manifested during the national elections.

Chairman of the Council for Responsible Political Behaviour Dr Bishnu Ragoonath, highlighted that two major political parties have engaged in racist rhetoric and race-baiting and have largely avoided responsibility for these divisive actions. He advocated for greater responsibility from political leaders and their parties, and greater respect for each other.

Dr Raymond Ramcharitar, writer and cultural historian, focused on anti-Indian racism, saying it was “built into the state and has been from the 19th century”. He criticised a post-colonial power structure made up of “creole citizens” (European, African and mixed race persons) who have, he said, treated Indians like outsiders and subjected them to “a stream of racist rhetoric” from the press, leading creole citizens and institutions. He compared the experiences of Indo-Trinidadians to African-Americans who have succeeded despite great discrimination. In a perhaps discordant note, but in the spirit of the legitimacy of free academic discourse, he pointed directly to the governing People’s National Movement (PNM) as the body that promotes the interest of this creole group which seeks to exclude Indo-Trinidadians.

Prof Reddock explained that the notions of “oppressor” and “victims” are no longer “black and white” in our post- colonial, multiracial society, obscuring who is the oppressed and the oppressor. Accordingly, the narratives of suffering and sacrifice become mechanisms through which nationalist ethnic mobilisation is manufactured, strengthening feelings of solidarity and community. This, she says, creates a much higher potential for conflict.

Language plays a central role in understanding the dynamics of race relations, said Dr Sheila Rampersad, journalist. Traditional race insults (the use of the “n-word” and the “c-word” to refer to Indo and Afro-Trinidadians, for example) may no longer be perceived as malicious, but terms of endearment. However, she questioned whether this is true, or whether people have become desensitised to the negative connotations of these words.

She suggested that Trinidadians view themselves as racial, not racist. The former is a neutral, but layered term, and its use indicates that Trinbagonians view their racism as a milder version of what occurs in “racist” societies. This, she reasoned, may be indicative of a lack of understanding about racism.

“We define many things as racist that are not, in fact, racist,” she said. “To merely speak the words marginalisation, alienation, discrimination, is to sometimes be racist. Trying to express feelings of disadvantage is to be racist. To be conscious about your ethnic ancestry is also automatically labelled racist.”

Ruqayyah Scott, youth activist and UWI student, drew attention to the struggles of biracial people who must contend with being neither “African enough” nor “Indian enough”. She urged that conversations about race relations should not be confined to the experiences of Indo and Afro- Trinidadians, but rather, should consider a wider scope reflective of the issues of multiracial T&T.

UWI Clinical psychologist Dr Katija Khan, provided strategies for greater inclusion. It is not enough for citizens to not be racist, she said, they must be actively anti-racist to combat racism. She proffered that safe spaces for honest and candid discussions, more research, political watchdogs and a reexamination of the education curriculum are needed. She echoed Prof Antoine’s warning of indirect race discrimination, which requires sensitisation if we are to address it in concrete ways.

An innovative feature of the symposium was the use of a web-portal on the Faculty’s webpage which allowed members of the public to share their experiences of racism to promote understanding. Some of these testimonials were read, demonstrating that feelings of exclusion and discrimination existed across a wide spectrum of peoples and there was a need for healing.

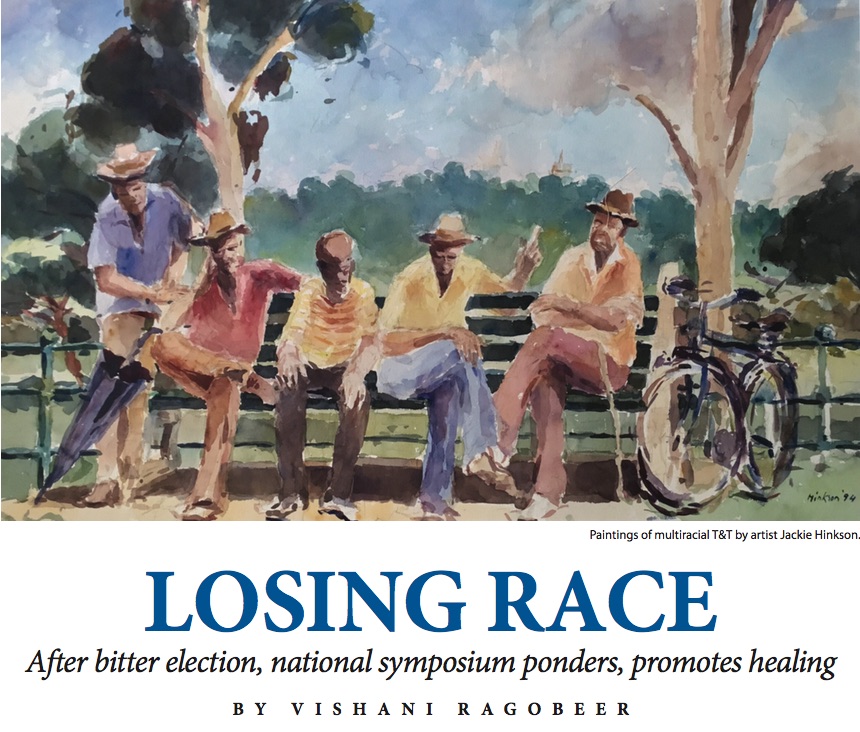

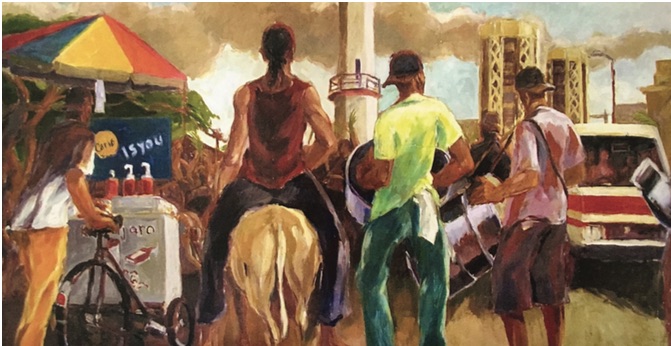

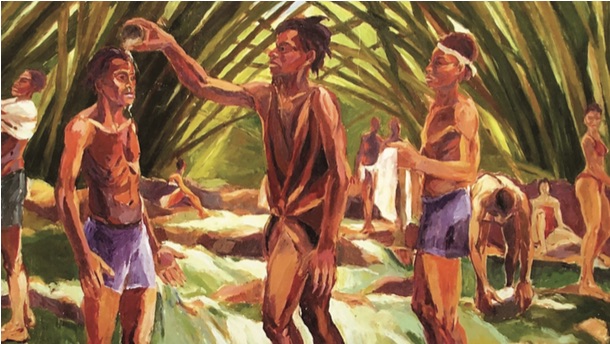

Participants were also treated to contributions from leading artistes, whom Prof Antoine described as the “conscience of the nation”. They echoed the need for unity. Novelist, Earl Lovelace read from his work Salt, reminding participants of “what it is to be human” [race]. Artist Jackie Hinkson shared paintings showing multicultural images of Trinidad and Tobago. Musical notes of Chinese, African, and Indian origin; pan; and a calalloo of the above, also filled the healing space.

The symposium attracted over 31,000 hits and lively debate on Facebook. There was consensus that honesty and empathy were needed and that the nation needed to move forward in unity.