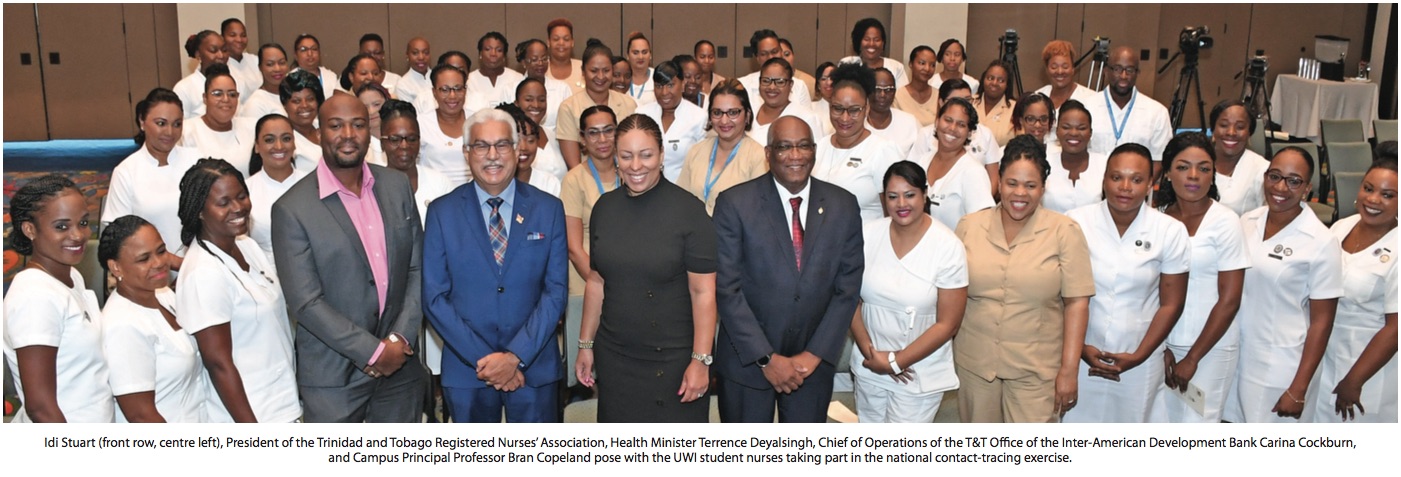

UWI nurses conduct COVID-19 contact tracing on behalf of the Ministry of Health

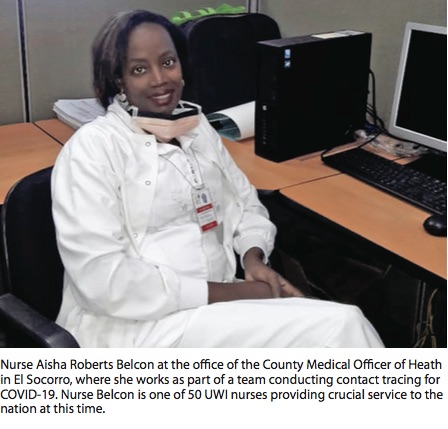

Registered nurse and midwife Aisha Roberts Belcon has always felt devoted to her profession. So when she was called on to participate in a countrywide coronavirus contact-tracing exercise last month, she was fully prepared for the mission.

Belcon, who is studying to become a District Health Visitor at the UWI School of Nursing (UWISoN), was one of 50 nurses who received scholarships from the Ministry of Health and were called to assist with the effort to track the spread of COVID-19.

Health Minister Terrence Deyalsingh announced the collaboration with UWI during a March 28 media briefing. The deadly pandemic has infected over 3.5 million people (at the time of writing) around the world. UWISoN Director Dr Oscar Noel Ocho, also a registered nurse (RN) and a graduate of The UWI’s Mona and St Augustine campuses, defines contact tracing as – “the process of identification of individuals who have had direct contact with someone who is diagnosed with an infectious disease, and making contact to ascertain their health status or recommend actions to remain disease free or seek help if they develop symptoms.”

“Since COVID-19, the virus associated with the coronavirus, is highly infectious,” he says, “it is important that individuals, exposed to persons who have tested positive, be contacted and quarantined.”

Internationally, evidence points to the effectiveness of contact tracing. Taiwan, which enacted a stringent regime of testing and tracing upon detecting its first case of COVID-19, recorded fewer than 400 cases and six deaths after three months. By contrast, the UK pivoted away from contact tracing to focus on containing disease spread in mid-March. Thousands of UK nationals, who had returned from vacation in hard-hit Italy, were not tracked. Britain has since seen some of the highest infection and mortality rates in Europe.

In terms of the Trinidad and Tobago initiative, Dr Ocho notes, “All persons involved are already qualified registered nurses and most have some level of post-basic qualification.”

Nurse Belcon and her cohort had their studies suspended in order to participate in the contact tracing exercise.

For the married mother of two, contact tracing methodology was “not a new skillset, just a new situation. The process of (monitoring) and processing patients” was already part of her training with regard to “any outbreak – like dengue, measles, or any communicable disease that you want to control very fast”.

Fifty of UWISoN’s qualified nurses, along with 50 trained volunteers from the Trinidad and Tobago Red Cross, were assigned to County Medical Officers of Health, and received instruction specifically geared toward battling the coronavirus. The trainees were then assigned to various health facilities, in order to trace patients and their contacts in different geographical areas.

Belcon was put to work in the St George Central region, encompassing Morvant, Laventille, Barataria, San Juan, and Aranguez.

She says patients become known to the health system through varying methods. “Some show up at the hospital, or they call the hotline or even the police station.”

Others were identified by border control agents monitoring international travel.

“If you’ve been exposed to someone who tested positive for COVID-19, it’s possible you picked it up. Ican’tletyougooutorgotoworkforthenext14 days,” says the RN.

Belcon has so far monitored the contacts of some four COVID-19 patients, “some who may have more than 50 contacts,” mainly adults, of all ages.

It is up to her to track down, call and visit them. When she cannot go in person, she reads a “legally binding” agreement over the phone and commits them to stay confined. She remains in touch with all of them by telephone.

Contacts receive certification, “such as a sick leave form, to show they did not abandon their job but were quarantined. Or, I call their bosses.”

“The main challenge,” she says, “is trying to convince people to do what they should do simply because it is the right thing to do. If need be, we can get the police involved, but we don’t want to do all that.”

“You will find that people have different levels of education, different levels of understanding, and people deal with things differently.”

But for the most part, contacted parties “have been compliant, even if they may have no symptoms”.

For those who do become ill, she advises they “take paracetamol, remain hydrated, stay away from others,” and occasionally get a bit of fresh air – alone – outside.

“But often, people are just lonely,” she says. “It’s ‘Moms’ and ‘Pops’ at home alone. Their children or grandchildren cannot come and see them, and they’re bored to tears. So sometimes your phone call is not just about health. You chitchat, you make little jokes and talk with them. Often, they are confined to one room. Their family may put in a TV, a fan, for them. They pass food inside for them, and they go and bathe at odd hours. So they are isolated. Some have young children who can’t understand why their parent can’t come out and play with them.”

Frustration does build up. She hears the complaints:

‘I’m locked up so long, I want to go outside!’ Those are the times that she plays on their emotions though some take more convincing than others. “You have to coax them, because you can’t force them. You try to get people to think and be responsible, not just for themselves, but for their family and the country too. In many homes, people live with extended families. And it’s your granny, grandpa, your mom, or your aunt who will feel the brunt of it.”

Belcon cautions against taking chances: “You may feel you can go out, smoke a cigarette, drink some beers. If you do catch it, it may be like a normal flu. Maybe so – for you – but it might not be so for others. It could be a matter of life and death for them. You never know – the shopkeeper could have it. And, because you had to get a pack of cigarettes, you could lose your grandma.”

Online shoppers are also at risk. “When you buy something off the internet, you have to interact with the delivery driver.” She adds with a wry laugh, “You may end up paying $19.99 for COVID-19!”

For Belcon, nursing is an indispensable part of healthcare. Some people think it’s all about medicine and technology. She knows first-hand that it is the human aspect - caring and compassion - that can make someone’s day or make the difference for their outcome.

The work is emotionally demanding, especially when “juggling parenting with the oath you made to patients”.

Add in “the lack of opportunities” for advancement in Trinidad and Tobago, especially when compared to colleagues whose nursing careers have blossomed abroad. “Friends encourage you to come up. They say, ‘Girl come, we can organise for you and the family’.”

But despite the allure of bigger salaries and better benefits, she is determined to remain in the country of her birth and to give her best right here at home: “If we all go, who will stay?”

She is hopeful with regard to the nation’s fight against COVID-19.

“I pray that people hold strong long enough for it to be effective, because it can become more stressful as time goes on. The fact is that most people survive. There is no need to panic if we stop it from spreading so that the vulnerable don’t get it.”

Dr Ocho is also cautiously optimistic, saying: “the current (small) number of persons who have been identified with community spread of the virus may be as a result of the effectiveness of the contact tracing, as (it may have led to) more persons who have been exposed quarantining themselves. This may account for the numbers being so low.”

He said the nurses “are expected to be engaged with the tracing effort (in the first instance) up to June 2020”.