|

March 2019

Issue Home >>

|

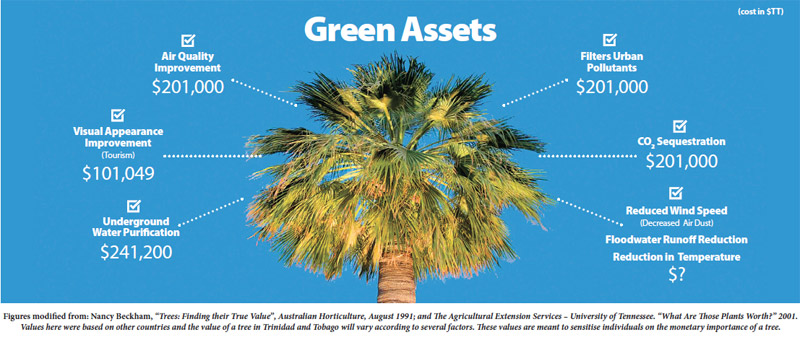

In today’s fast paced world, only commodities with high monetary value are deemed important by society. To some, trees may be considered the only sustainable building product that can be found anywhere in the world, while to others, they are often viewed as one of many raw-materials used to manufacture “important” products. But have you ever wondered how much an individual tree costs? Much to the surprise of many, an average tree surviving approximately 50 years is worth an estimated TT$1.2 million dollars (Das. 1979; Treecycling. 2018).

Trinidad and Tobago has a range of habitats for a family of plants that are an outstanding green investment – palms. Palms are flowering monocotyledon evergreen trees, shrubs and climbers that only grow in the tropics. They are the most cultivated plant group in the world, next to the cereals (rice, wheat and corn). The palm is considered the “prince of the plant kingdom” since they have some of the largest seeds of any plant group in the world, most of which are edible. Trinidad and Tobago is treasured by many botanists for its range of habitats that support interesting palm species.

Trees mitigate air quality and storm water risk

Trinidad and Tobago, being one of the few industrialised Caribbean economies, should be very cautious about managing urban storm water and municipal air quality, and should follow other developed countries that spend millions of dollars mitigating air quality and urban storm water risk in cities. For example, according to RAND Corporation, heavy smog and fog blankets in most cities in China cost the Chinese economy trillions of dollars annually, not to mentioned kills approximately 1.5 million people yearly (CNBC 2016). In the Caribbean, millions of dollars are lost due to raging urban storm waters as a result of passing tropical waves (particularly in Haiti, Cuba, Dominica, the Bahamas, and in recent times Trinidad).

The island of Trinidad represents the northernmost distribution of moriche palms (Mauritia flexuosa), while both islands represent the southernmost distribution of the Cocothrinax genus. Palm ecosystems in Trinidad and Tobago play an integral part in air purification, carbon sequestration, flood water retention, water purification and aquifer replenishment, which benefit local communities immensely. Healthy palms such as the moriche palm and royal palm (Roystonea oleracea) can grow for well over 150 years; hence one can only imagine the value of these palms given the many ecological services they provide throughout their lifespan.

Plant palms along highways

With the establishment of the Trinidad and Tobago Green Council Building (TTGBC) in 2010 and the support of private recycling companies such as, Recycling in Motion (RIM) and Caribbean Battery Recycling Limited (CBRL), we have already taken steps toward “sustainable development”, however there is much more to be done since commercial and residential buildings are increasing by the day; clogging underground water systems and reducing air quality within our cities and on our highways. I propose that we focus more heavily on sustaining our “green assets” throughout urban areas while we are in the “green”. This would save future governments millions.

Additionally, native palm trees should be favored over exotic trees as they are slender and tall, ideal for growing in urban environments where space may be a limiting factor. Planting indigenous palm species is better for several reasons. Often, exotic trees do not live as long as local palms and require much more maintenance work (such as consumables, equipment and manpower to irrigate, fertilise, apply pesticides, prune, trim and dispose of branches).

I propose planting local palms along highways. On the medium strip, solitary high fire-tolerance, medium single-stem palms should be planted—for example Gru-gru boeuf (Acrocomia aculeata). Along the side strips, high fire-tolerance larger palms capable of surviving in degraded lands should be planted—for example the cocorite palm (Attalea maripa). The decision as to what palm species should be planted along what highway needs to be carefully considered by the people and governments; factors such as wildfire hazard, undesirable wildlife and insect establishment should be considered during the decision making process, amongst other constraints.

But despite these relatively minor constraints, planting palms is a more than worthwhile investment. Imagine a world, years from now, when the citizens of Trinidad and Tobago can drive along the highways and enjoy not only the majestic beauty of our palm trees, but also the benefits of cleaner air and less risks of flood. That’s the kind of world we should leave for succeeding generations. And we can. The time is now.

Linton Arneaud is a PhD candidate in environmental biology at the Department of Life Sciences. He is currently a teaching assistant at the department. |